What This Episode Covers

Episode 12 traces how asbestos solved the braking problem — and how that solution created an occupational invisibility trap affecting hundreds of thousands of workers for half a century. The episode opens with a mathematical fact: 15 million Model T cars were built between 1908 and 1927. Each one needed brake replacements. That's tens of millions of exposure events happening across factories, assembly lines, independent garages, and home driveways. But the workers doing this work were never counted, never studied, never protected.

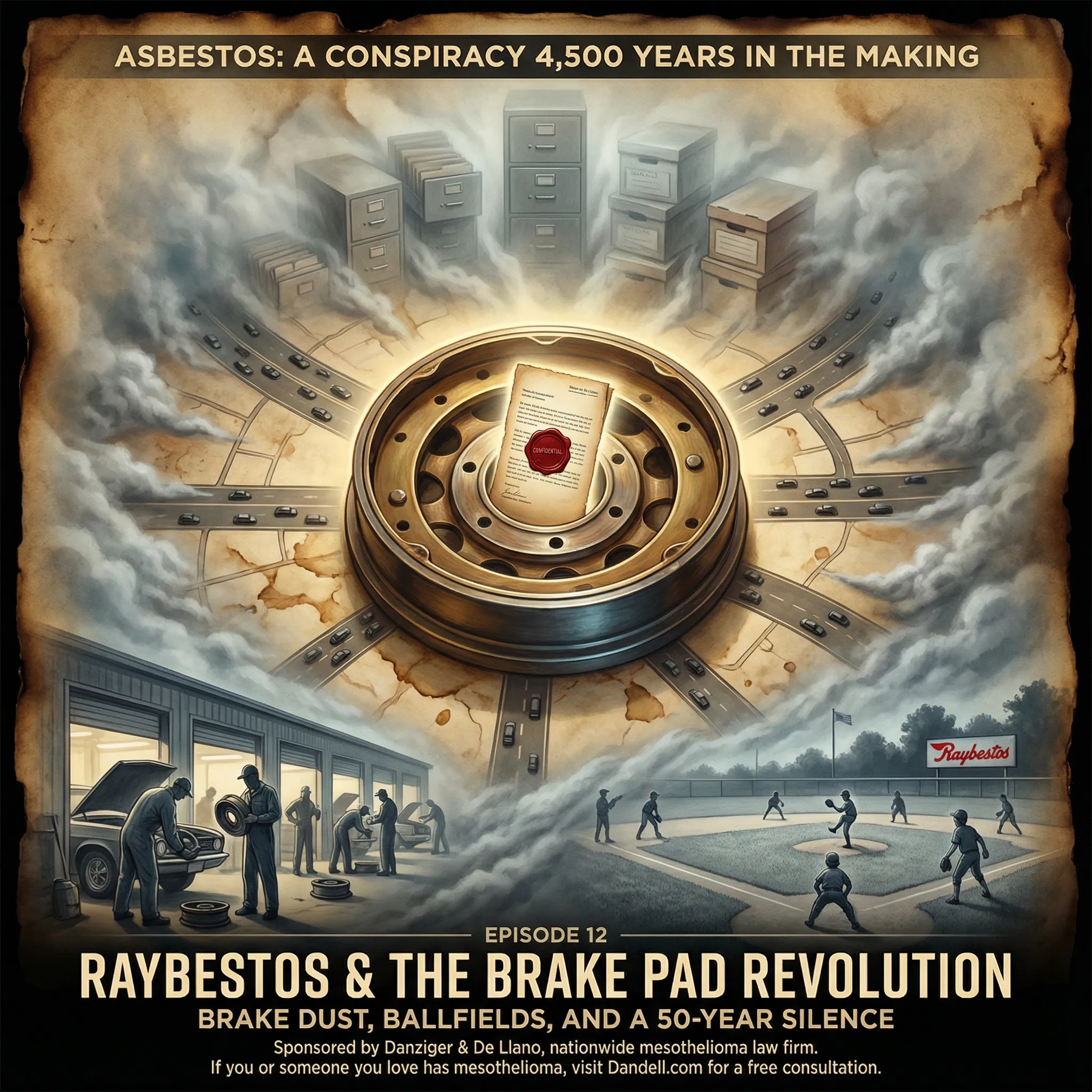

The technical story is straightforward: pre-asbestos brakes failed catastrophically. Wood blocks, cotton soaked in oil, leather, camel hair — all degraded under sustained heat. When Louis Renault invented the drum brake in 1902, the engineering problem remained unsolved: how do you maintain friction when temperatures exceed 400°C? Asbestos was the answer. Thermal stability to 450°C. High friction coefficient. Fire resistance. And crucially: it was cheap. In 1906, Arthur Raymond and Arthur Law patented their woven asbestos-copper wire mesh lining in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The company name tells the story: Raymond + asbestos = Raybestos. Within a decade, Raybestos became the dominant brake lining supplier. Ford initially used Raybestos, switched to cotton around 1910, then switched back to asbestos as vehicle speeds increased. By the 1920s, Raybestos was the de facto standard.

But the occupational story reveals a more troubling pattern: the workers fixing these brakes were invisible to the companies selling them. Factory workers, assembly workers, independent mechanics, home mechanics — an estimated 900,000 people by 1975 — none were included in corporate health studies. E.R.A. Merewether identified the brake work hazard in the early 1930s. The first successful lawsuit against a brake manufacturer came in 1985, filed by an 81-year-old retired mechanic who won a $2 million verdict. Forty-seven years after the hazard was documented, the legal system finally held someone accountable. Meanwhile, in Stratford, Connecticut, the Raymark facility was contaminating neighborhoods with asbestos waste, creating the highest mesothelioma rates in the state — including cases among children who played on sports fields built on 270,000 cubic yards of contaminated fill.

The complete episode transcript with citations, key facts, and additional context is available on WikiMesothelioma.com — our open educational resource for asbestos and mesothelioma information.

Meet the Team Behind This Episode

Senior Advocate

Senior Advocate specializing in military and shipyard exposure cases. Helps veterans navigate VA benefits and claims.

Executive Director of Client Services

18+ years mesothelioma advocacy. Host of the MESO Podcast. Lost his own father to asbestos-related lung cancer.

Related Resources

Topics

Were You or a Loved One Exposed to Asbestos?

The history in this episode isn't just history. If you worked with asbestos products, lived in a home built with asbestos materials, or were exposed through a family member's work clothes, you may have legal options. Danziger & De Llano has spent 30+ years and recovered nearly $2 billion for asbestos victims.