What This Episode Covers

The asbestos industry didn't discover asbestos dangers — they inherited documented evidence. In 1898, Lucy Deane, one of Britain's first female factory inspectors, wrote a government report describing asbestos's "evil effects" and its "sharp, glass-like jagged nature." Her words were published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office. That same year, Henry Ward Johns — the entrepreneur whose name would define the world's largest asbestos manufacturer — died of asbestosis at age 40. And Dr. Murray examined a dying textile worker at Charing Cross Hospital, documenting asbestos fibers in the lungs. Three independent institutional warnings in a single year.

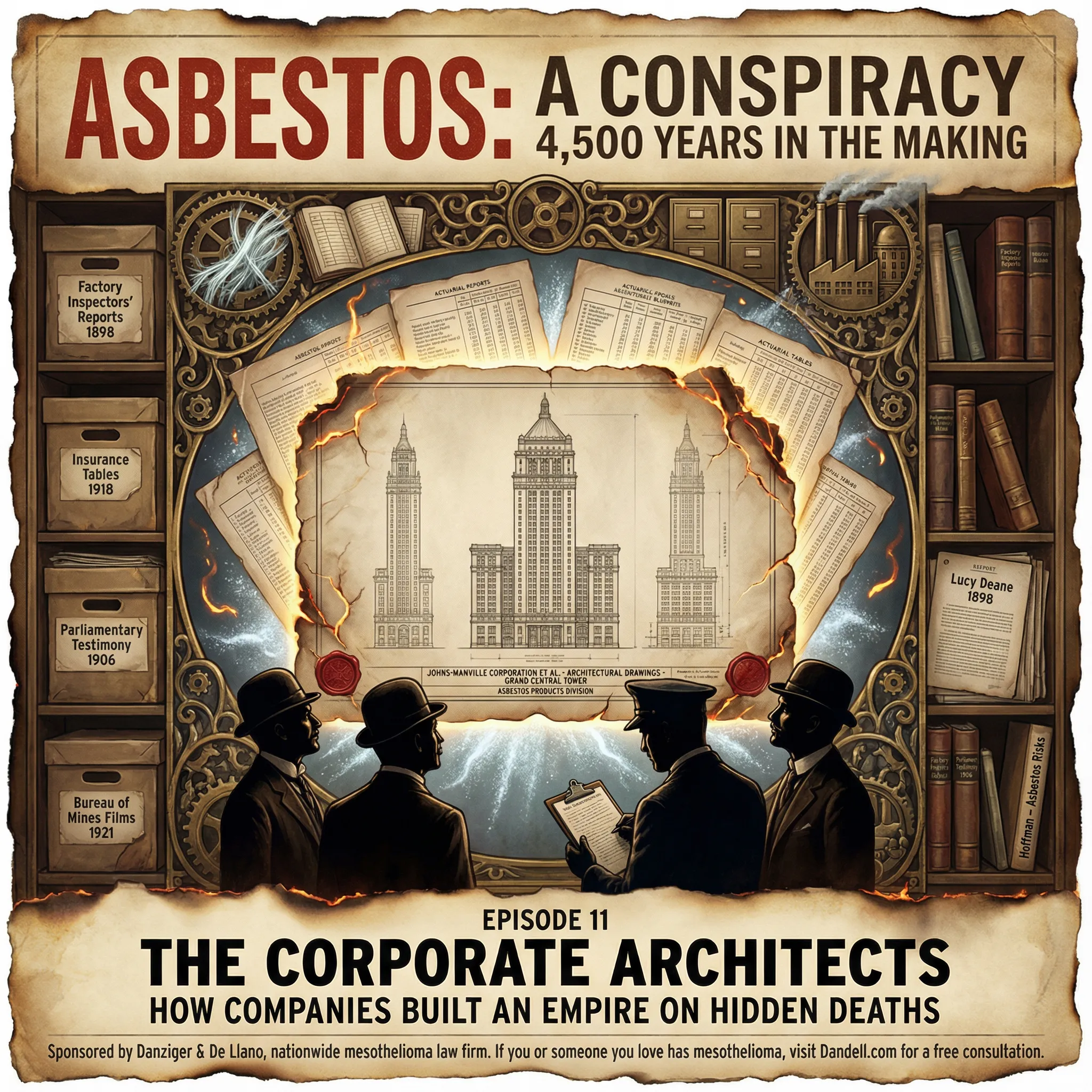

This episode traces how Johns-Manville was built on a foundation of documented hazards. T.F. Manville created the company in 1901 — exactly three years after Johns's death from the disease that the company would manufacture for the next century. By 1906, Parliament heard testimony from Dr. Murray describing dead workers and autopsy evidence. They added six occupational diseases to the compensation list. Asbestos wasn't included. By 1908, insurance actuaries — Frederick Hoffman at Prudential Insurance — had calculated that asbestos workers were a statistical liability. Insurance companies declined coverage. But the knowledge stayed confined to regulatory and actuarial circles. Workers didn't know. In 1921, the U.S. Bureau of Mines produced a 67-minute silent film marketing Johns-Manville to schools, churches, and civic organizations. Government institutions coordinated with manufacturers to distribute propaganda through channels of public trust.

The corporate architects of the asbestos industry operated with extraordinary institutional precision. They weren't discovering dangers — they were managing information. Female factory inspectors documented hazards because women did the dustiest jobs. Regulatory systems documented cases because workers died. Insurance actuaries documented risk because actuaries calculate mortality. But each institution operated in isolation. The connection between Lucy Deane's report and Henry Ward Johns's death wasn't made publicly. The connection between Parliament's testimony and Johns-Manville's government-backed marketing wasn't explicitly stated. Information was distributed across regulatory channels, actuarial tables, and government film reels — everywhere except to workers. By 1901, Johns-Manville controlled the industry. By 1926, Turner Brothers had 5,000 employees. By 1961, Turner Brothers had 40,000. The industry had been built on perfectly documented evidence of harm, managed through institutional compartmentalization.

The complete episode transcript with citations, key facts, and additional context is available on WikiMesothelioma.com — our open educational resource for asbestos and mesothelioma information.

Meet the Team Behind This Episode

Founding Partner, Danziger & De Llano

Princeton graduate with corporate defense background. Specializes in statute of limitations, evidence preservation, and corporate liability.

Founding Partner, Danziger & De Llano

30+ years of mesothelioma litigation. Former CPA bringing financial expertise to asbestos trust fund claims.

Related Resources

Topics

Were You or a Loved One Exposed to Asbestos?

The history in this episode isn't just history. If you worked with asbestos products, lived in a home built with asbestos materials, or were exposed through a family member's work clothes, you may have legal options. Danziger & De Llano has spent 30+ years and recovered nearly $2 billion for asbestos victims.